Can a Gallery Walk Be Readings and Images

5 great enquiry 'tuning in' strategies for students of all ages

Senior teacher Ben Reeves (BR) and Primary teacher Emma Perrett (EP) demonstrate the power of engaging students' curiosity, no affair what age.

Tuning students in to the concepts or large ideas of a new course of learning is different to merely introducing a new topic.

In the words of inquiry expert Kath Murdoch, "it'due south about tuning in to students' thinking." It is a chance to honour what they bring to the inquiry, to unearth prior experiences, surface current thinking and create meaningful contexts that will enable the formation of new knowledge, understanding and connection.

Students are never too young or too former to tune-in. Equally human being beings, we love to exist at the beginnings of a journey. We look ahead with feelings of hope, possibility, the promise of discovery as we venture into the unknown.

Withal we besides know from our ain experience that what is meaningful is motivating, and when we are given a stake in shaping our own learning, nosotros feel more engaged, more purposeful and more willing to put in endeavour.

Perhaps nigh importantly, to see 'how far I have come' I demand to inquire 'where have I come from?' Tuning in can surface the initial, visible prove for students to see the continuous growth of their learning.

Hither are five great tuning-in strategies that foster opportunities for student appointment and encourage their natural marvel every bit co-creators of learning.

1. Mystery Artefact (or Stimulus Artefact)

What is it?

In that location is nothing like a mystery object to spark wondering and excitement.

Artefacts are concrete, physical things that are (or once were) embedded in a world of relations, meanings, processes or events.

Considering of this, they are highly evocative to imaginative suppositions, hypothesis, or inferences about questions of use, value, context, culture, perspective, belief or significance.

Instead of announcing 'this is what nosotros're studying adjacent', artefacts can prompt students to begin imagining and discovering a earth of learning for themselves.

Examples

Contrasting objects

Philosopher Rob Wilson uses contrasts betwixt familiar and unfamiliar objects to spark deep conceptual discussions. He once presented a bag, and a figurine (non these pictures, but real objects), and asked two simple questions:

- What is this object?

- What is its value?

The noise between the two objects naturally raised a whole range of unlike ideas, inferences and further questions, such as: what gives something value? Distinctions betwixt use-value and aesthetic value. The relationship between civilization, beliefs and value. Unintended consequences of some values on others (eg. plastic and pollution).

Students often come up with surprising and divergent thinking.

While this was intended to spark involvement in problems of 'value' in philosophy, it's not difficult to see how this aforementioned technique could engage students in bug of value in historical understanding, economics, English, or art interpretation. (BR)

Quondam fashioned objects

Rather than beginning a unit by announcing, 'this term, we're going to learn about the topic of communication and engineering', the teacher arrives with an onetime-fashioned telephone. She asks three questions:

- What is this object?

- How do you lot recollect it works?

- What might it tell us virtually how people lived or communicated to others in the past, compared to how we practise now?

For some teachers, information technology may exist surprising that our counterpart history is actually quite strange to a native of the digital globe.

By anchoring students in the past through a detail technological artefact, they have a specific reference point to begin wondering about the deeper conceptual relationships between engineering, homo relations, and social change. This tin can be farther enriched by having students bring back stories of their parents' or grandparents' memories of using these objects, and what the globe was similar so. (BR)

Provoking thoughts and wonderings through a mystery artefact is particularly pertinent for primary students when tuning in to the transdisciplinary theme of 'Where nosotros are in place and time'.

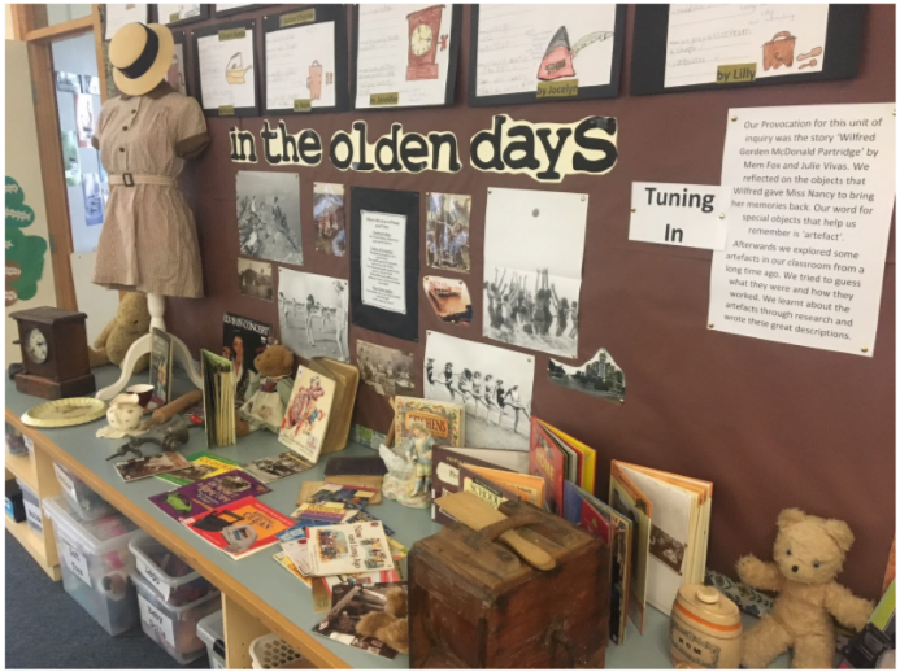

Prep teachers Leah Opie and Sarah Johnston used a variety of olden day objects to spark curiosity at the offset of their unit of inquiry on how 'Our lives today reflect the by generations'.

After reading the story 'Wilfred Gordon McDonald Partridge' by Mem Fox and Julie Vivas, students reflected on the objects that Wilfred gave Miss Nancy to bring her memories dorsum. Afterwards, they explored some olden day artefacts in the classroom.

Looking through the key concepts of grade and connection, students were asked to endeavor to estimate what the artefacts were and how they worked. Some students thought the old radio may be a hairdryer and the mincer could be a horn.

Later examining the olden day artefacts, the students wrote near what the object was, what it was used for, described its advent and then reflected on what we use today that meets the same purpose. (EP)

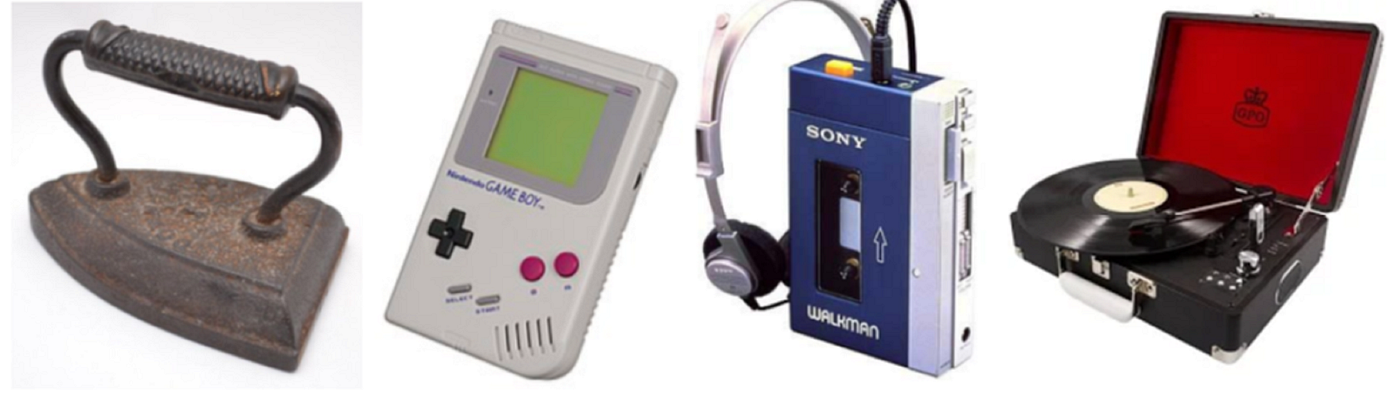

Sparking marvel and intrigue with an old-fashioned artefact tin can exist achieved with students from all ages and many dissimilar subject areas. During a Year 5 unit of inquiry nether the transdisciplinary theme 'How the earth works', I presented the students with a multifariousness of objects to capture their attention, create a sense of excitement and evoke deep thinking and questioning.

The central thought of the unit was 'The changing demands of club determine the development of inventions'. To hone in on the evolution of different inventions, I wanted to have the students dorsum in history to find out where many of our modern inventions first began.

Many students were able to make connections, while others were viewing these objects for the very first time. The rich discussion that ensued was memorable as students shared their experiences, made assumptions and asked thought provoking questions to deepen their understanding of how inventions have evolved and changed over time. (EP)

Artefacts of item significance

Imagine you are a professional appraiser on the Antique Road Bear witness. Someone arrives with this mysterious key. All they know is that it might accept something to do with the Civil Rights Movement in America. How would you lot go well-nigh researching this object, in gild to respond the questions:

- What might information technology unlock?

- What is its possible historical value or significance? https://tinyurl.com/y93rvo5g

This is the scenario that teacher Josh Ajima used to introduce a unit on Ceremonious Rights and Martin Luther Rex.

Non only does the object surface students' prior knowledge, it does so in a way that encourages initial imaginative inferences, hunches, hypothesis. It too focuses students on the concept of a inquiry strategy.

Josh set up a blueprint template so students could 3D print replicas of the historic key. This as well served equally a model for students to then research, design and create their own 3D mystery object challenge.

Doesn't that sound like fun?

Objects can accept all kinds of significance, in unlike subject field areas and contexts. Imagine giving the metaphors in a poem over to students every bit real, tangible objects to explore for their associations and significance? Or a option of different kinds of wheels, to spark marvel about the mathematical notion of Pi? (BR)

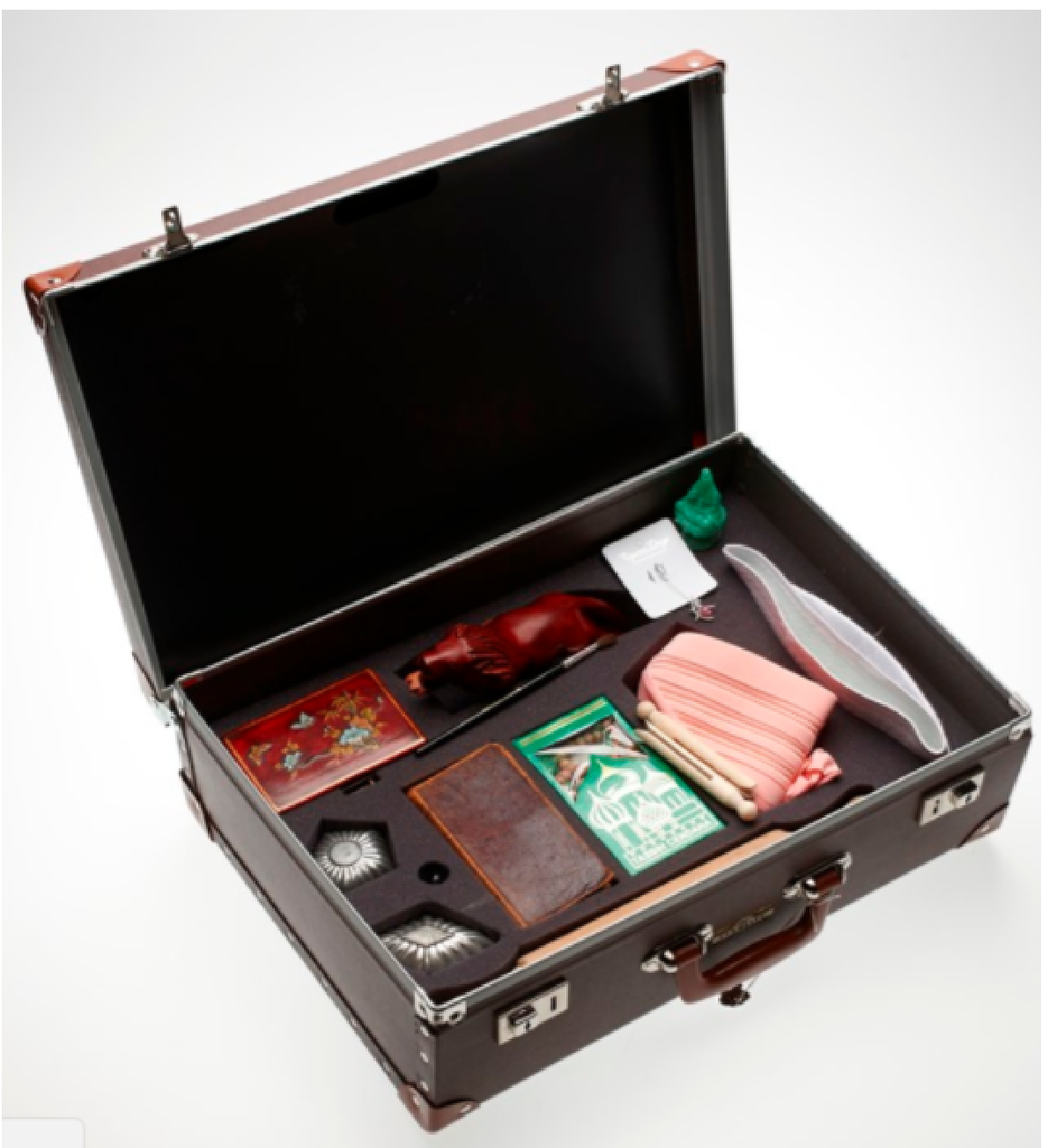

During an upper primary unit of measurement on Migration, I presented the students with a suitcase containing objects, artefacts, photos, diary entries, maps, and so on. Students were intrigued and began to excitedly explore the mystery suitcase, seeking to uncover who it belonged to and discovering the owner's migration story. (EP)

Tips and Tricks:

- Make sure you lot are articulate about your role & purpose equally a facilitator during the tuning-in process — that is, to surface rich student ideas, meanings, prior knowledge. A mystery object could easily turn into a game of 'guessing what'southward in the instructor'due south caput'.

- Objects need to be advisedly selected and appropriate, to spark curiosity in line with the engagement purposes, concepts and connections with the unit.

- Documenting initial ideas gives the teacher a wealth of information about how students are making pregnant, levels of conceptual understanding, gaps in factual knowledge or skills, all giving directions well-nigh where students can exist further challenged.

2. Wonder Wall (See, Think, Wonder)

What is information technology?

This thinking routine from Harvard Projection Zip is so effective in stimulating students' marvel relating to an area of study. It works by presenting students with a rich stimulus, similar a painting or an prototype, and asking three simple questions. Each question builds on the other, surfacing 3 dissimilar nonetheless interrelated kinds of thinking:

- What do you run into?

Encourages close ascertainment and utilize of descriptive language, by uncovering and noticing 'what is there'. - What practise you think is going on?

Takes thinking from description to initial inference-making, as students begin to hypothesise about the situation, the story, or how something might have come about. If y'all want to broaden student ideas from the stimulus, you can ask, 'what do you think about that?', geared more to surfacing initial opinions. This might work, for example, if the image depicts something controversial. - What exercise you wonder? (Or, 'what are you puzzled about?')

Having students ask questions helps to develop their dispositions towards curiosity and the expectation of further research. Questions likewise enable a re-date, every bit students circle back to the details, pondering their meaning, and opening up possible significance.

Examples

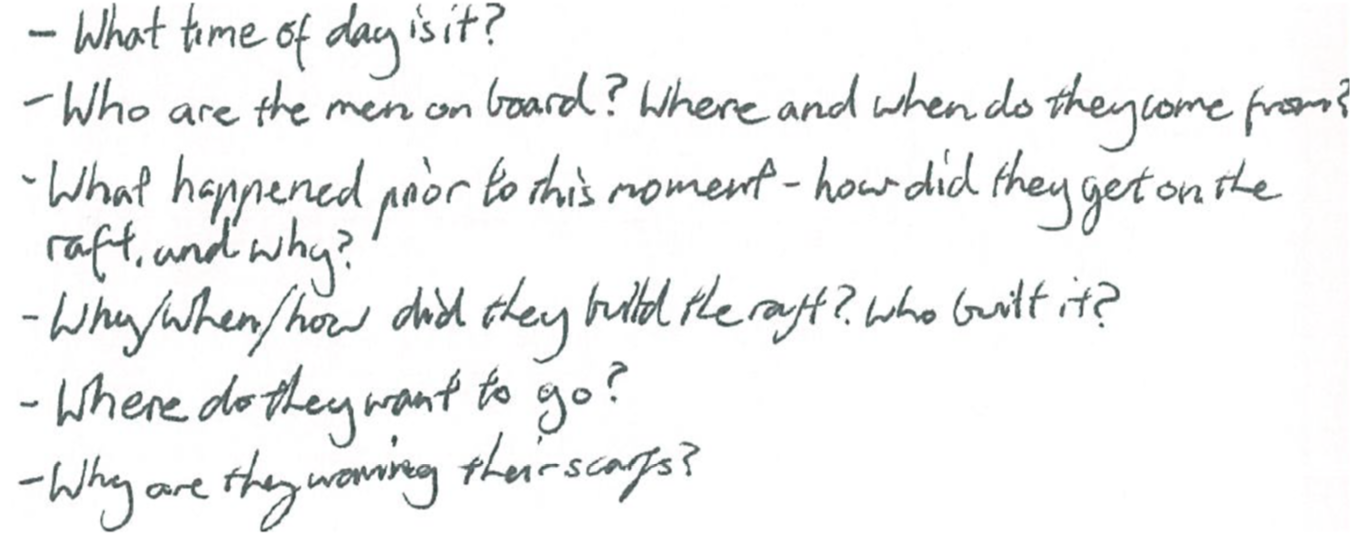

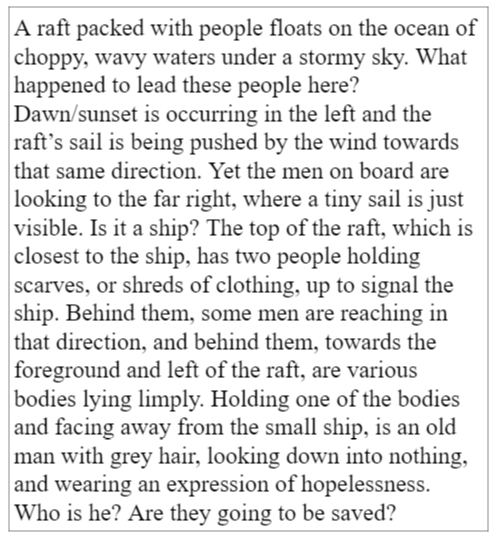

I used this image in a year 10 English class to engage students with the process of estimation.

The richness of the Raft of the Medusa stimulus enabled usa to tedious things downwards, especially the initial question — 'what do you run into?'

As students notice and share details, they also see what they might accept missed. For case, hearing one student point out the tiny send on the far horizon, others proclaimed, 'wow, I didn't detect that…'.

As the class collectively builds details and hypothesis most 'what is going on', farther questions naturally emerge. Hither is one student's list of questions:

This student had originally missed the item of the tiny ship, and was able to connect this to their question near the 'waving scarfs', raising further ideas and discussions about the human capacity for promise.

We could so venture into deeper ideas cartoon on these details: for example, what might exist the significance of the scale of the human gestures, compared to the scale of the ship?

In terms of our focus, this rich collective exploration enabled us to and so segue into a metacognitive level, every bit we discussed the role and importance of each of these types of thinking in the process of creating interpretations.

We could so transfer and apply these insights and techniques to other examples in poetry. As students internalise thinking structures, they tin can begin to use them independently equally conscious strategies in other situations.

I also had students produce a summary piece of writing that combined their descriptions, inferences and wonderings, afterward the discussions. This tin provide a baseline understanding for farther explorations into perspectives, contexts, themes, or artistic features. Here is an example of a student's summary: (BR)

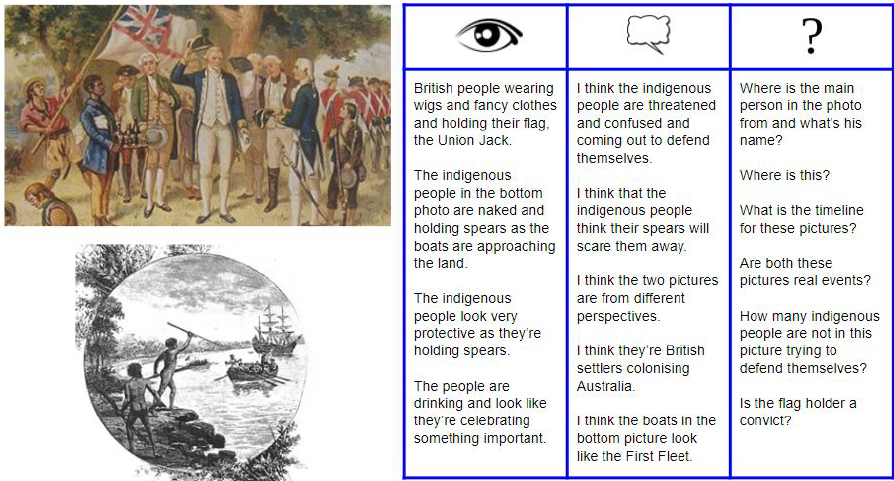

I used these 2 images (below) during a year 5 unit inquiring into the impact of colonisation on indigenous cultures. Both pictures depict the British colonisation of Australia from different perspectives — that of a white colonial settler contrasting with the perspective of Indigenous Australians. In the initial 'I see' investigation, students were encouraged to only place what they could see in the pictures rather than expressing feelings or thoughts.

From these observations the students were then asked to make inferences nearly what they thought about the images. Using the contextual cues in both pictures, the British flag and the boats of the First Armada, students delved deeper into the pregnant backside the images and a rich discussion ensued nearly how the same event can exist viewed from dissimilar perspectives.

Students then had the opportunity to wonder and ask questions about the images. These questions were then used as a reference signal throughout the unit of research equally students were able to respond their initial wonderings and reflect on how their learning had shifted and inverse. (EP)

Tips and Tricks

- Having students write downwardly their seeings, wonderings and questions ensures that each person has had a chance to recall for themselves and offer something to share.

- Ask students to write down other noticings (things they might non have seen) in a unlike colour, during the discussion. This helps them to build rich details and admit the commonage contributions of others.

- Encourage students to inquire further into their questions. This can be an particularly useful fashion of springboarding students into the initial exploration of a unit, giving them a sense of agency and purpose.

3. Circle of Viewpoints

What is it?

This is a thinking routine from Harvard Project Zero that makes visible the various perspectives embedded in a stimulus, text, effect or phenomena.

Every bit part of a tuning-in approach, surfacing a multiplicity of viewpoints tin help students to frame their initial thinking in relation to others, begin to appreciate complexity, and map out the terrain for further questions, ideas or investigations.

Instance

A circle of viewpoints can follow on really well from initial 'encounter, recollect, wonder' descriptions. Students tin brainstorm to make a bridge betwixt identifying item perspectives, and the abstract ideas or values they may represent.

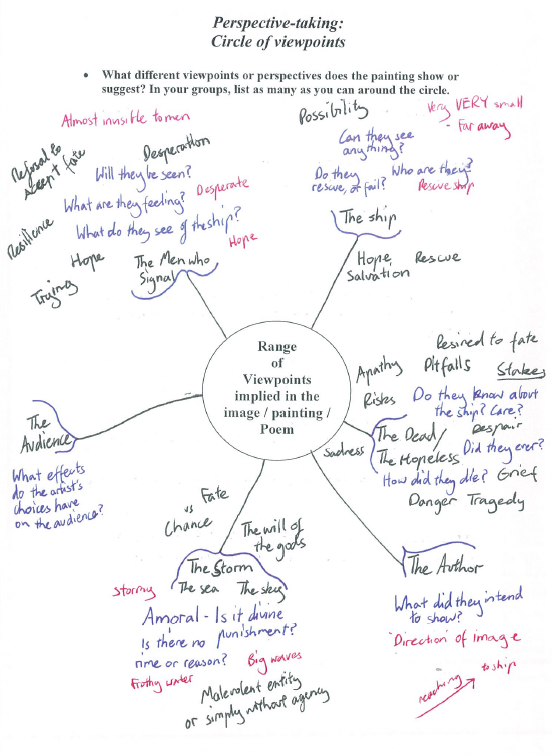

This example follows on from the previous Raft of the Medusa stimulus:

Find how the students are firstly identifying the concrete features of unlike viewpoints, adding layers of illustrative details, so using these as springboards into generating more abstract thematic ideas, such equally 'hope', 'grief', 'fate vs take chances'. (BR)

The circle of viewpoints thinking routine is very effective when students are looking at something through the conceptual lens of perspective. The post-obit case was taken from an inquiry into different forms of expression. Students viewed a variety of art forms and using the circumvolve of viewpoints routine, investigated how different people/groups perceive or experience about that art form.

The stimuli used for the example in a higher place was a picture of graffiti. This particular pupil discussed his personal perspective and then looked at the viewpoints of the police/regime, the public and graffiti artists. (EP)

Tips and Tricks

- Having students move from the concrete to the abstract helps them to discover ideas, deeper meanings or significant concepts for themselves.

- Take the opportunity to employ the circle of viewpoints as a focus for discussion, enabling further elaborations of student thinking and the unpacking of ideas.

- One time students begin to recall at the abstract or conceptual level, the teacher can continue to press for supporting detail, reinforcing the important relationship between evidence and ideas.

- A circle of viewpoints can also be a corking springboard into creative, belittling or exploratory writing, as well as providing opportunities for students to generate their own investigative questions.

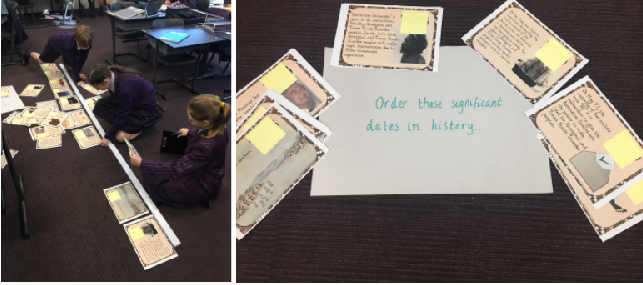

4. Silent Gallery Walk

What is it?

A silent gallery walk is an interactive classroom exhibit of meaningful questions, documents, images, problem-solving situations, texts and/or video clips.

Students walk through the gallery documenting their observations, thoughts, questions and opinions on the various graphic or textual displays, just as 1 might walk through an art gallery viewing artwork.

Students must interact with each exhibit in a purposeful fashion.

Choose a topic or concept that will evoke meaningful responses and claiming the students to question or deepen their thinking.

Students are to rotate through the gallery and will have a set amount of fourth dimension to interact, contribute to and think near the stimuli at each exhibit. They may pose their ain questions or merely respond or add to another student'south thoughts and feelings.

This thinking routine may culminate in a whole grade word, small-scale group reflection, leave slip or descriptive writing piece.

Example

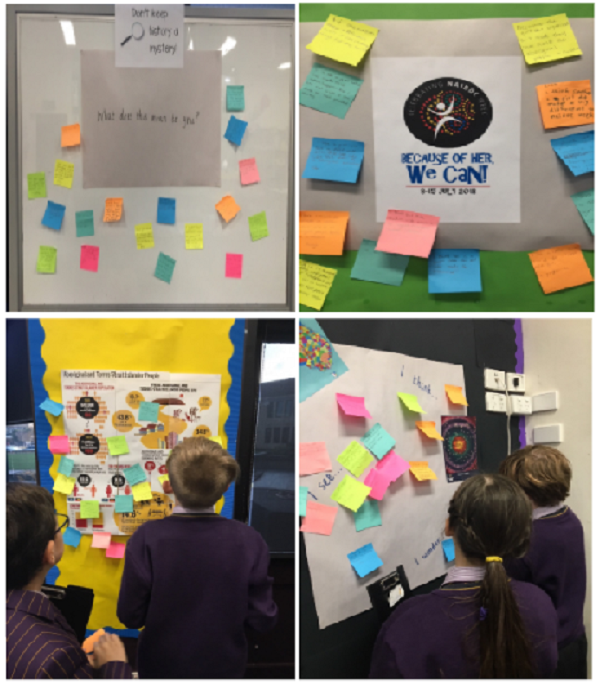

To celebrate NAIDOC (National Ancient and Islanders Day Observance Committee) Week, I prepare a Silent Gallery Walk in my Year 5 classroom.

I specifically chose a range of stimuli to celebrate the history, civilization and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

There was no word prior to this tuning in activity equally I wanted to spark marvel and let the students the opportunity to share prior experiences, question their understandings and view these exhibits without any preconceived ideas or answers.

At the conclusion of the silent gallery, we began to unpack each exhibit as students shared their ideas, thoughts and wonderings. (EP)

Tips and Tricks

- It is important to explain to the students that a Gallery Walk is to be done in silence, simply like walking around an art gallery. This is a quiet activity.

- This strategy may be used when yous desire to take students share their work, examine important historical documents, view news reports, respond to quotations or inquire thought provoking questions.

- As this strategy requires students to physically move around the room and collaborate with stimuli, it tin can be especially engaging for kinesthetic and hands-on learners.

- Displays can be hung on walls or placed on tables around the classroom. Each exhibit needs to be far enough away from others then that students tin evenly disperse effectually the room.

v. Provocation

What is information technology?

Emotions are not only powerful motivational tools, they are also signals that we intendance nearly something that matters in the earth. A skillful provocation jolts us into a state of affairs of challenge, discomfort or racket, where nosotros must encounter or negotiate other responses, other perspectives, and exist for a fourth dimension in a land of exciting, unresolved tension.

Examples

Co-ordinate to the tradition, Gyges was a shepherd in the service of the king of Lydia. At that place was a groovy tempest, and an earthquake fabricated an opening in the earth at the identify where he was feeding his flock.

Amazed at the sight, he descended into the opening, where, among other marvels, he beheld a hollow brazen equus caballus, having doors. Peering inside, he saw a expressionless trunk, with nothing on merely a gold ring.

This he took from the finger of the dead and reascended. He discovered it could brand him invisible.

With great haste, he traveled to the royal metropolis. Equally soon equally he arrived he seduced the queen, and with her help conspired against the king and slew him, and took the kingdom.

Would y'all, like Gyges, 'do equally y'all pleased' with a magic ring that fabricated you invisible, and be a "God among men"? (Plato, Republic)

This is the provocation I presented to my twelvemonth eleven International Baccalaureate (IB) philosophy class, every bit part of our tuning-in to the report of Plato's Republic. Most at once, stories of imagined lives of unfettered freedom began to fly around the classroom.

Students who attached themselves to virtue were chop-chop challenged by others, "as if y'all wouldn't…", vying together with the discomfort of looking into the mirror of their own moral selves.

The discussion delved into deeper questions nigh human nature.

Distinctions began to emerge between personal morality, legal systems, upstanding frameworks.

We delved into the origins and assumptions of contract theories of justice.

All of this emerged from the students' ain guided dialogue, equally they came to articulate the key questions of the text:

- What is justice?

- Does it pay to be virtuous?

Provocations are a smashing way to appoint students' emotions or imaginations, as they authentically grapple with the large questions of a text or unit of measurement of study, marking the first of a journey for afterward reflections and travels of deeper understandings. (BR) (Run across a farther exploration of this example here: https://medium.com/@ben.reeves_62533/the-aboriginal-art-of-dialogue-10d3543d3a1c)

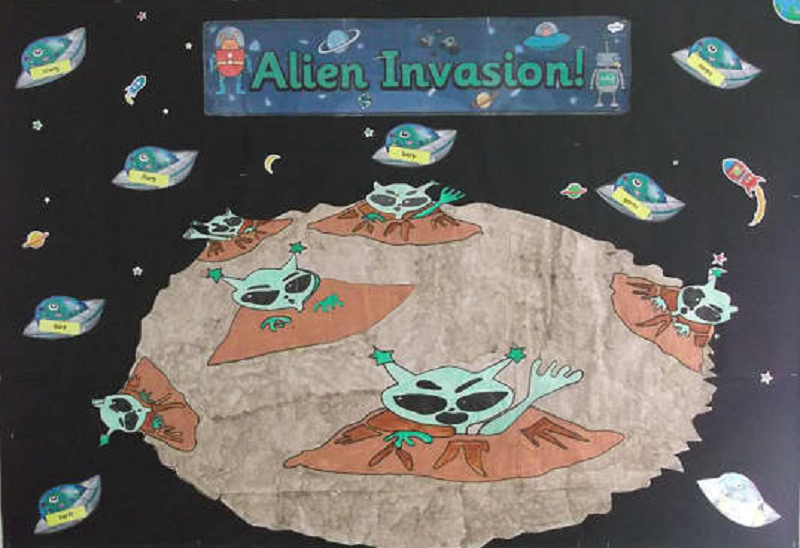

Tuning students in to a unit of inquiry about the impact of migration and the settlement of new colonies on indigenous cultures, I wanted to provoke my learners' interest by creating an experience they would never forget.

The most powerful provocations ofttimes involve borer into the important concepts of a unit — in this example, settlement, invasion and ownership.

I began to reflect on these concepts and was taken back to my own personal experience of owning my first home. I felt an overwhelming sense of pride and achievement. If my new business firm was invaded and taken over by some other family, I would have felt a devastating loss.

I couldn't even brainstorm to fathom the incredible loss the Indigenous Australians must have felt, when British settlers colonised Australia. How could I replicate such a feeling in my students?

The provocation involved explaining to the students that due to unforeseen circumstances, the ii Year 5 classes would be swapped, and the teachers switched.

We were halfway through the schoolhouse yr and the children had already formed such a close bond with me as their teacher. They also felt a strong sense of identity in the classroom as their work adorned the walls and they had played an active part in the design of the learning space.

Swapping teachers and moving classrooms to some was catastrophic, while for others it prompted contemplation about what this would mean, and how they would cope with this sudden change and upheaval.

Information technology wasn't long before the other grade 'invaded' the classroom leaving students feeling lost and afraid.

Every bit teachers, we knew in that moment that our purpose had been accomplished. We wanted the students to experience what it would feel like to have something really important and valuable taken away from them.

While this provocation sparked confusion and discomfort, it also stimulated imagination and curiosity.

It was important to end this scenario with a debrief session and so that students could vox how the feel fabricated them feel. They were and so able to draw on this experience throughout the unit of measurement when discussing the impact of colonisation on indigenous peoples.

When students can make a personal connectedness to the concepts being explored, the learning becomes fifty-fifty more enriching and meaningful. This experience was one that was then memorable for students, they continued to talk well-nigh it for the remainder of the year. The concepts of settlement, invasion and buying were seemingly entrenched in their minds.

Tips and Tricks

- Information technology is of import for provocations to elicit a personal connection between students and the concepts being explored. Students tin can so move towards transferring their conceptual understanding to the bigger ideas in a unit of enquiry.

- Provocations tin take place throughout a unit to engage students in thinking and questioning. While they are a wonderful way to melody students in to a new research, the nigh important thing is that they leave a lasting impression that students can reflect on and connect to their learning.

- Give the students time to discuss and reflect on the experience. Provocations are intended to provoke or claiming one's thinking and information technology is of import to respect that students may need this time to debrief and express their feelings and emotions.

All of these tuning-in approaches offer immense opportunity for dialogue, discussion and questioning, equally we seek to cultivate one of the about important dispositions for students of all ages —the spark of marvel.

This article has been a collaboration between Ben Reeves and Emma Perrett.

Ben Reeves writes in the areas of education, philosophy and fiction. Current labors of beloved: Masters of Didactics — researching the assessment of 21st Century skills, first YA novel, and a tiny boat. https://twitter.com/BDReeves

Emma Perrett is an IB PYP teacher, lifelong learner and Ed-tech geek. She is inspired by all things inquiry, cultivating learner agency in her classroom and unlocking the magic of learning.

mathewsigntearame.blogspot.com

Source: https://medium.com/@ben.reeves_62533/5-great-inquiry-tuning-in-strategies-for-students-of-all-ages-3044ac1cd2d9

Publicar un comentario for "Can a Gallery Walk Be Readings and Images"